The number of middle-income seniors will nearly double in 10 years. And more than half of them won’t have the resources to pay for housing and care.

When “The Forgotten Middle,” a National Investment Center (NIC) funded demand study conducted by NORC at the University of Chicago, was released in April, its conclusions and accompanying resources and research caused a shock wave. Headlines such as “Middle-income seniors risk falling through the cracks” told one side of the story.

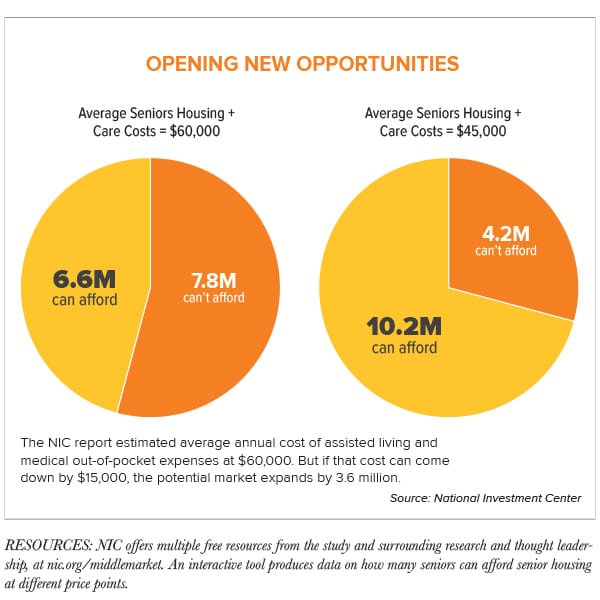

But there’s another side that soon surfaced: Opportunity. For every notch down in projected cost, the market grows by leaps. NIC defines middle-market for seniors from 75 to 84 as those who have annual financial resources between about $25,000 and $74,000; from age 85 up, it’s $24,500 to $95,000.

One of the measurements, for instance, projects the average annual cost of assisted living rent and medical out-of-pocket costs to be about $60,000. By this measure, by 2029 only 6.6 million seniors—19 percent—could afford it. But if the industry can bring the annual cost down to $45,000 annually, the market opens wide—to 10.2 million seniors.

The goal of the study was two-fold, says Bob Kramer, founder and strategic advisor at NIC: To shed light on a social issue, but also to “highlight a huge underserved market opportunity.”

He finds it exciting—and he’s looking forward to the creativity that will emerge as the industry works to meet the need.

What Can’t Change: Quality

The study results were “not surprising to strategic-thinking providers,” says Charles Trefzger, Affinity Living Group CEO. Some of these thinkers have served the middle market for years—and there’s a lot to learn from their experience. Often, what they share goes counter to intuition (but aligns with common sense).

The first middle-market myth to topple is that a lower price means a decline in quality. Middle-market residences must offer the same level of quality as those priced higher. The place to make the difference is in the volume of services, not in performance, Trefzger says.

The provider needs to have an established culture of efficiency, of looking for places not to cut corners, but to cut what’s unnecessary, and knowing how to tell the difference. The culture should also be open to change and innovation to put into practice quickly new ideas that improve quality and cut costs.

A multi-brand approach, similar to hotel chains that have different brands at different price points, is one model quick to emerge. Others look at segueing from multi-family to middle market senior living. But pulling models from other industries isn’t as simple as it seems. “If you’re serving a need-driven group, you can’t compromise on the care,” Kramer says.

“The labor and care component is the hardest nut to crack. And that’s where technology plays a significant role.”

More data, more savings: The middle-market resident of the future will likely be surrounded by screens and sensors (and at ease with them). Sensors are already opening up worlds of data, the kind that can shave time from caregivers’ tasks and allow them to practice more personalized service.

The cohort of middle-income seniors is also predicted to have a greater instance of multiple chronic health conditions, so technology advances such as fall prediction technology, floor and door sensors, and lighting programming may be essential to preserve their well-being and keep their health care costs down.

Technology investments aren’t limited to tools that assist health and well-being; they’re critical to getting the economies of scale in operation that make cost efficiencies possible.

Technology investments that save time and money require a company-wide culture, Trefzger says—no silos allowed. “It’s got to be an ecosystem, or it fails.”

No more bells and whistles: To get more affordable senior living, increase the square footage. Sounds strange? Jon Fletcher, vice president at Presbyterian Homes & Services (PHS) told why turning the typical “shrink to save money” approach on its end works.

For middle-market residence, a slightly larger (1,000 square feet) apartment feels more like home—there’s not the shock of moving from a detached house to a tiny “unit.” This decreases turnover and makes marketing easier. Recoup for this by using builder-grade fixtures and carpeted floors, for instance.

The chandeliers and soaring atriums that characterize some high-end senior living design aren’t going to cut it in this market. Listening to prospective residents and doing market research can save a misstep. Middle-market residents, Kramer says, are willing to give up some things, but they may not be the ones operators expect.

Scale and centralize: Both Affinity and PHS are vigilant about operating efficiencies. From resilient landscaping to a shared call center for all communities, they hunt for ways to get better services for less: management, food purchasing, billing, marketing, and more.

Scale and centralize: Both Affinity and PHS are vigilant about operating efficiencies. From resilient landscaping to a shared call center for all communities, they hunt for ways to get better services for less: management, food purchasing, billing, marketing, and more.

Trefzger predicts regional providers will be at an advantage as the middle market grows, because they can more easily scale and centralize. PHS does the same, using a hub-and-spoke model with central shared management capacity at the hubs.

Tackle policy: It’s difficult to see a way to serve the middle market without addressing the Medicaid spend down policies.

“The regulations were designed with good intentions, but they make it difficult to serve and provide an affordable product to the middle market,” Kramer says. “Someone could have spent 50 years as a nurse, or trade union worker, or first responder, and their only choice ends up being, ‘Sorry, you have to shed every asset that you worked for and be labeled poor.’”

“Boomers aren’t having it—not to mention the impact that would have on Medicaid,” Kramer says. “We’ve got to figure this out.”

Don’t forget your mission

“We are first and foremost caregivers, so focus on caregiving,” Trefzger says. “That’s where the middle market needs us to be.”

NIC plans to continue to highlight providers serving this market who can share knowledge and experience.

The study notes that by 2029, the average Boomer will be only 83 years old—two years shy of the average entry age to assisted living. “The next 10 years present an opportunity for the industry to broaden its target market, create new and innovative seniors housing residences, and prepare for the years after 2029, when the nation’s massive senior population will need these options the most,” the authors write.

Kramer points out that while the study stops at 2029, the trend continues: “This is the future: The middle-income cohort will grow, and the lower-income one will shrink, for another 20 years.”

In fact, both predict the middle market will become the new normal in senior living, with other diverse offerings filling out the market. “The middle will be forgotten no more,” Trefzger says.